Writing a legal essay isn’t about sounding smart or cramming in fancy words. It’s about showing that you understand the law, can think critically, and know how to build a strong, logical argument.

Most law students don’t write bad essays because they’re not smart. They write bad essays because they’re trying to do too much — or worse, trying to sound “legal” instead of being clear.

You want your reader to trust you from the first paragraph. That trust comes from clarity, structure, and purpose — not Latin phrases or quoting Lord Denning like it’s gospel.

Let’s walk through the deeper, time-tested advice — the kind you only learn after doing this for years.

This guide will walk you through exactly how to do that — step by step — with simple, practical advice and real examples of what works (and what doesn’t).

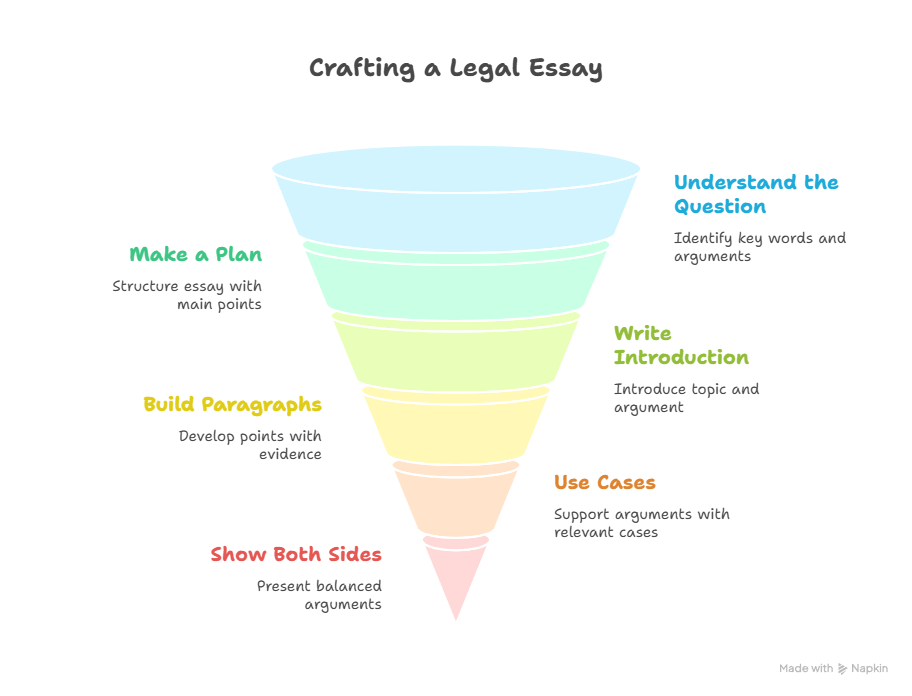

Step 1: Understand the Question (Really Understand It)

Before you write anything, make sure you know exactly what the question is asking.

Legal essay questions often look simple, but they’re not. They use words like “critically discuss,” “to what extent,” or “evaluate,” and those words matter.

Here’s what to do:

- Underline key words in the question.

- Figure out what you need to argue.

- Break the question down into smaller parts.

Example:

Question: “Critically evaluate whether judicial review is effective in upholding the rule of law.”

What they really want:

Do you think judicial review works well to protect legal limits on power? What’s good about it? What are the problems?

Don’t just explain what judicial review is — show what it does well, what it doesn’t, and how that affects the rule of law.

Step 2: Make a Quick Plan

Planning isn’t optional. A short plan helps you avoid repeating yourself, drifting off-topic, or writing a messy essay.

A good plan should include:

- 3–5 main points you want to make.

- Examples or cases you’ll use for each point.

- A basic structure: intro, body, conclusion.

Example Plan (for the judicial review essay):

- Intro: What judicial review is, and your main argument.

- Strengths: Enforces limits on government (Miller, Factortame).

- Weaknesses: Courts can be too cautious (Evans case), hard to access judicial review.

- Impact on rule of law: Sometimes strong, sometimes limited.

- Conclusion: Overall, helpful but not perfect.

Step 3: Write a Clear, Focused Introduction

Your introduction should be short but strong. Think of it as your essay’s opening pitch. You’re telling the reader:

“This is what I’m arguing. Here’s why it matters.”

What to include:

- One or two sentences explaining key terms.

- A clear answer to the question.

- A preview of the points you’ll cover.

Example:

Judicial review helps courts check that the government follows the law. In many cases, it protects the rule of law by holding public bodies accountable. However, it’s not perfect — access is limited and judges often avoid political decisions. This essay will explore both sides to show that judicial review is useful, but not always effective.

Step 4: Build Strong Paragraphs — One Point at a Time

Each paragraph should make one point, support it with evidence, and explain why it matters.

Use this structure:

Point → Evidence → Explain → Link

Good example:

One way judicial review supports the rule of law is by holding ministers accountable. In Miller (2017), the Supreme Court ruled that the government could not trigger Brexit without Parliament. This showed that even the Prime Minister must follow legal rules. It also sent a strong message that big political moves still need proper legal backing.

What not to do:

Miller showed that the Prime Minister broke the law. Judicial review is important. There are other cases like Factortame and Evans. Judicial review has helped.

This second version is too vague. No clear point. No explanation. No impact.

Step 5: Use Cases and Statutes — But Only When They Help

Cases are important, but don’t just list them. Use them to prove a point.

Do this:

- Pick relevant cases.

- Explain what happened briefly.

- Show why it supports your argument.

Avoid this:

- Name-dropping 10 cases in one paragraph.

- Quoting long passages from judgments.

- Writing a case summary with no analysis.

Step 6: Show Both Sides — Then Take a Stand

Law isn’t black and white. The best essays show both arguments and explain which side is stronger and why.

Use phrases like:

- “However…”

- “On the other hand…”

- “It could be argued that…”

Then explain your position.

Example:

Some argue that judges are too cautious and avoid big political cases. In Evans v Attorney General, the court sided with releasing Prince Charles’s letters — but only after a long fight. This shows courts can be slow or reluctant to challenge government secrecy. Still, even limited intervention helps protect legal accountability.

Step 7: Write a Strong Conclusion

Don’t just repeat your points. Your conclusion should:

- Answer the question clearly.

- Sum up your position in one or two sentences.

- Leave the reader with your final thought.

Example:

Judicial review is not a perfect tool. But despite its limits, it plays a key role in keeping public power in check. It gives people a way to challenge unfair decisions and makes government actions more transparent.

Step 8: Check and Edit — Always

Once you’ve written your essay, take 10–15 minutes to check it.

What to look for:

- Spelling and grammar.

- Clarity — are your sentences easy to follow?

- Structure — does your argument flow clearly?

- Relevance — does each paragraph answer the question?

Don’t:

- Leave in vague phrases like “it’s kind of important.”

- Repeat the same point in different words.

- Rely on fancy words to sound academic.

A great legal essay isn’t about sounding impressive — it’s about thinking clearly, arguing logically, and backing up what you say with real legal reasoning. If you stay focused, plan properly, and explain your points clearly, you’ll do far better than most.

Here are the 4 points you need to keep in mind:

- Don’t write to impress — write to persuade.

- Don’t tell me what happened — tell me why it matters.

- If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it yet.

- Plan. Write. Re-write. Edit. Polish.