Learn how contracts are formed in India, from offer to agreement, with key steps and examples under the Indian Contract Act, 1872.

Contracts are a part of our everyday lives, whether we notice them or not. From hiring a freelancer to signing up for a gym membership or even buying a house, all of these involve a legal agreement—commonly known as a contract.

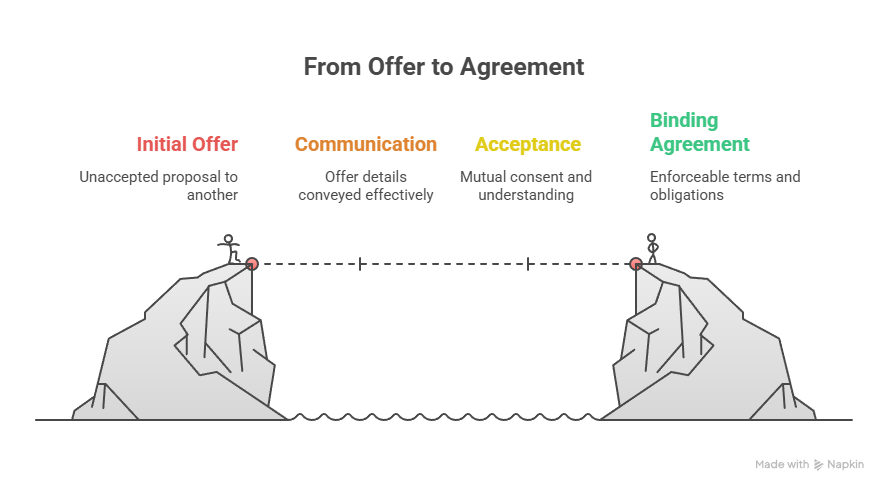

But how exactly is a contract formed? What are the ingredients that make it valid and enforceable under Indian law?

Let’s walk through the entire process step by step, using a relatable example along the way. By the end, you’ll see how a complete contract is formed from scratch—and how each stage connects back to the Indian Contract Act, 1872.

Step 1: The Offer or Proposal

Relevant Section: Section 2(a), Indian Contract Act, 1872

Every contract begins with an offer. An offer, or proposal, is when one person expresses a clear willingness to do or not do something, with the intention of getting the other person’s agreement.

It’s important that the offer is specific and clear—vague statements or casual suggestions don’t count.

Let’s take an example:

Aman is a freelance graphic designer. One day, he approaches Bharat, who owns a new restaurant. Aman says, “I can create your restaurant’s full branding and menu design package for ₹25,000.”

That’s a valid offer. It’s clear, definite, and made with the intention of forming a business arrangement.

Step 2: Acceptance

Relevant Section: Section 2(b)

An offer means nothing without acceptance. The person receiving the offer must agree to it clearly and without changing the terms. If they say, “I accept, but can you also add a logo for free?”—that’s not pure acceptance. That would be a counter-offer.

Continuing our example:

Bharat replies, “That sounds good to me. Let’s go ahead with the ₹25,000 package. You can start next week.”

Now the offer has been accepted. Once an offer is accepted, it becomes a promise.

Step 3: Intention to Create Legal Obligations

Not specifically codified, but recognized by Indian courts

A key factor that distinguishes a contract from a casual agreement is the intention to create a legal relationship. If two friends agree to meet for coffee, that’s not a contract. But if two businesses agree to exchange services and payment, that’s serious.

In our example:

Aman wants to be paid for his design work. Bharat expects professional-quality branding. This is clearly a business transaction with financial implications. Both parties intend for this agreement to be legally binding.

Step 4: Lawful Consideration

Relevant Section: Section 2(d)

For a contract to be valid, both sides must give and receive something of value. This is known as consideration. It doesn’t have to be money—it could be a service, product, or even a promise.

Back to Aman and Bharat:

Aman is providing design services. Bharat is paying ₹25,000. Both parties are offering something valuable to the other. This exchange forms the consideration for the contract.

Step 5: Capacity to Contract

Relevant Section: Section 11

Not everyone can legally enter into a contract. To be eligible, a person must:

- Be at least 18 years old

- Be of sound mind

- Not be disqualified from contracting by any law

In our case:

Aman is 27, and Bharat is 29. Both are competent adults running their own businesses. They have the legal capacity to contract

Step 6: Free Consent

Relevant Sections: Sections 13 to 19

Consent must be given freely. If someone is forced, misled, or threatened into agreeing, the contract is not valid. The law is clear: any kind of coercion, undue influence, fraud, misrepresentation, or mistake can make a contract void or voidable.

What about Aman and Bharat?

There was no pressure, deception, or misunderstanding. Both understood the terms and agreed willingly. The consent was genuine.

Step 7: Lawful Object

Relevant Section: Section 23

The purpose of the contract must be legal. You can’t make a contract for something that’s against the law, goes against public policy, or is immoral.

Our example holds up well:

Designing branding for a restaurant is a perfectly legal activity. So, the object of the contract is lawful.

Step 8: Certainty and Possibility of Performance

Relevant Section: Section 29

The terms of a contract must be clear enough to be understood and carried out. Also, the performance of the contract should be practically possible. If the promise is too vague or impossible to perform, the contract is not valid.

Aman and Bharat agreed that Aman would provide a full branding and menu design package within two weeks, and Bharat would pay ₹25,000 on delivery. That’s specific, measurable, and feasible. This contract satisfies both certainty and possibility.

Step 9: Writing and Registration (When Required)

While most contracts under Indian law can be oral, some types of contracts must be in writing (e.g., agreements involving immovable property, long-term leases, or high-value sales).

In this case:

Though not legally required, Aman and Bharat decide to put their agreement in writing to avoid any future disputes. They draft a short, clear contract outlining the scope of work, payment schedule, and delivery timeline.

This written document provides evidence of the contract.

Step 10: Execution and Performance

Relevant Section: Section 10 (Enforceability)

Once all the elements are in place and the parties begin to act on the terms, the contract is in effect. When both parties fulfill their obligations, the contract is said to be executed or performed.

Here’s how it ends:

Aman completes the branding work within the agreed time. Bharat is satisfied and transfers the ₹25,000 as promised. The contract is fully performed, and the transaction is complete.