Whether you’re hiring a freelancer, renting an apartment, or buying something online, chances are you’re entering into a contract—whether you realize it or not. Contracts are the foundation of daily transactions and business relationships. But for a contract to be legally binding, it must meet certain basic requirements.

In this post, we’ll break down the essential elements of a valid contract in plain, simple language. Whether you’re a business owner, freelancer, or just someone wanting to protect your rights, this guide is for you.

1. Offer and Acceptance

The first essential element of a valid contract is a lawful offer by one party and a lawful acceptance of that offer by the other party. Section 2(a) of the Indian Contract Act defines a proposal (offer) as a willingness to do or abstain from doing something with a view to obtaining the assent of the other party. Section 2(b) defines acceptance as the assent given to the proposal.

An offer must be clear, definite, and communicated to the offeree. Acceptance must be absolute and unqualified. A counter-offer amounts to rejection of the original offer. Communication of both offer and acceptance is vital. Only when acceptance is communicated properly does a contract come into existence.

Example: If A offers to sell his motorcycle to B for ₹50,000, and B agrees without any conditions, a valid agreement is formed. If B says he will pay ₹45,000 instead, it is a counter-offer, not an acceptance.

Case Law: In Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Co. (1893), the court held that a general offer made to the public can be accepted by anyone who fulfills the conditions.

2. Lawful Consideration

Section 2(d) of the Act defines consideration as something in return. For a contract to be valid, there must be consideration from both parties. Consideration is the value (monetary or otherwise) exchanged between the parties, and it must be lawful. Unlike English law, Indian law recognizes past consideration as valid.

Consideration need not be adequate, but it must be real and lawful. Agreements without consideration are generally void, except under specific exceptions provided under Section 25, such as those made out of natural love and affection or made in writing and registered.

Example: If A agrees to sell his laptop to B for ₹20,000, the payment is consideration for A and the laptop is consideration for B.

3. Capacity to Contract

Section 11 of the Indian Contract Act states that every person is competent to contract who is of the age of majority according to the law, is of sound mind, and is not disqualified from contracting by any law to which he is subject.

A minor (a person below 18 years), a person of unsound mind, or a person disqualified by law (e.g., an undischarged insolvent) cannot enter into a valid contract. Any contract with a minor is void ab initio.

Example: If a 17-year-old enters into a contract to buy a mobile phone on EMI, the contract is void and cannot be enforced.

Case Law: In Mohori Bibee v. Dharmodas Ghose (1903), the Privy Council held that a contract with a minor is void ab initio and cannot be ratified after the minor attains majority.

4. Free Consent

According to Section 13 of the Act, consent means that both parties must agree upon the same thing in the same sense. Section 14 states that consent is free when it is not caused by coercion, undue influence, fraud, misrepresentation, or mistake. If consent is obtained by any of these means, the contract becomes voidable at the option of the aggrieved party.

Coercion (Section 15) involves using force or threats. Undue influence (Section 16) arises when one party is in a position to dominate the will of the other. Fraud (Section 17) and misrepresentation (Section 18) involve providing false information. A mistake (Sections 20–22) must relate to a fundamental fact for the contract to be void.

Example: If a sick person is forced to transfer his property to a relative under pressure, the contract can be voided due to undue influence.

5. Lawful Object

Under Section 23, a contract must be made for a lawful object. The object of the contract must not be illegal, immoral, or opposed to public policy. If the object is unlawful, the agreement is void.

An agreement to perform an illegal act, such as committing a crime or engaging in corruption, is not a contract at all.

Example: A agrees to pay B ₹1 lakh to steal confidential business data. This agreement is void because the object is illegal.

6. Intention to Create Legal Relationship

An agreement must be entered into with the intention of creating legal obligations. Social and domestic arrangements usually lack such intention and are not enforceable in a court of law.

Commercial agreements are generally presumed to have legal intention unless explicitly stated otherwise.

Example: If two friends agree to go for a trip together, it is not a contract. But if a businessperson agrees in writing to supply goods for a price, it clearly indicates an intention to create legal obligations.

7. Possibility of Performance

A contract must be capable of being performed. An agreement to do something impossible is void under Section 56 of the Indian Contract Act.

If the object of the contract becomes impossible after the agreement is made, due to reasons beyond the control of the parties, the contract is discharged on the ground of frustration.

Example: A contracts to supply goods from a warehouse that burns down before delivery. The contract becomes void due to impossibility of performance.

Conclusion

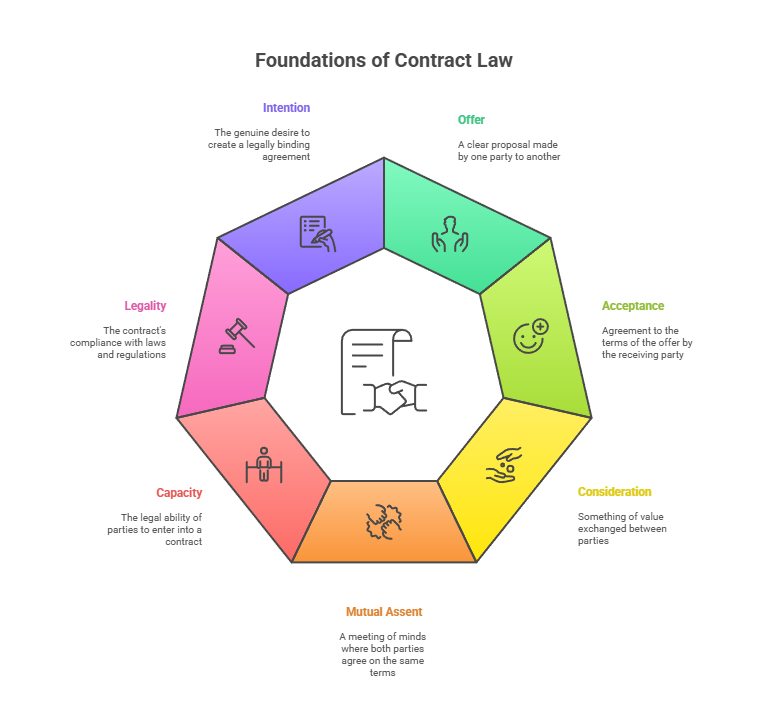

To summarise, a contract under Indian law must contain the following elements: offer and acceptance, lawful consideration, capacity to contract, free consent, lawful object, intention to create legal relationship, and possibility of performance. Absence of even one of these elements may render the contract void or voidable.